Hund's rule — Electrons also go by bus

Just like humans when we get on a bus, electrons also have rules and quirks when choosing their place in the atom. Discover what they are in this article!

QUANTUM

BeyondTheCMB

1/1/2025

Atoms are made up of two main parts: the nucleus, which contains protons and neutrons, and the orbitals, where the tiny electrons can be found. But something you might not know is that these electrons don’t just go anywhere—they have habits and preferences that are surprisingly similar to the ones we humans have when choosing where to sit on a bus.

The orbitals and the floors of the bus

Imagine you live in London, a city famous for its iconic red double-decker buses. You’re waiting at your stop, and when the bus arrives, it’s completely empty—you can choose any seat you like.

Which one would you choose?

If you were just a tourist in London, I’m sure you’d choose the upper deck — like an excited child, you'd head upstairs to enjoy the views of the city. But if you were a regular commuter who takes this bus every day of the week, you’d probably stay on the lower deck — climbing those narrow stairs is just too much effort! It’s much easier and more comfortable to remain downstairs. And that’s exactly what electrons do: they fill the different "floors" of the atom based on how much effort—or energy—it takes to occupy each one.

The floors of the bus represent the different orbitals of the atom — the regions where electrons can be found. Just like regular bus passengers, electrons will first occupy the orbitals that require the least effort — the ones with the lowest energy. But, what determines how much energy each floor has?

n, the distance from the nucleus of the atom: or the height of the floor. The lower the floor, the less energy it adds to the total. For example, the first floor (n = 1) has less energy than the second floor (n = 2) because of this effect. Each floor has an assigned name: s (n = 1), p (n = 2), d (n = 3), f (n = 4), g (n = 5).

l, the shape of the orbital: or the number of seats on the floor. In atoms, the shape of the orbital determines how much rotational energy the electron has, since it defines how the electron spins. The more pairs of seats available on a floor, the larger it has to be, and therefore the more “effort” it takes to find a spot in it.

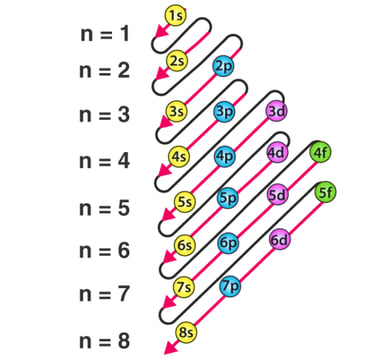

In this way, the energy of each floor can be compared by adding the number of seat pairs on the floor and the height of the floor. An orbital will have more energy than another if its (n + l) value is greater than that of the other orbital.

Here below, I’ll show you the shape of the orbitals on each “floor” and the order in which they fill up:

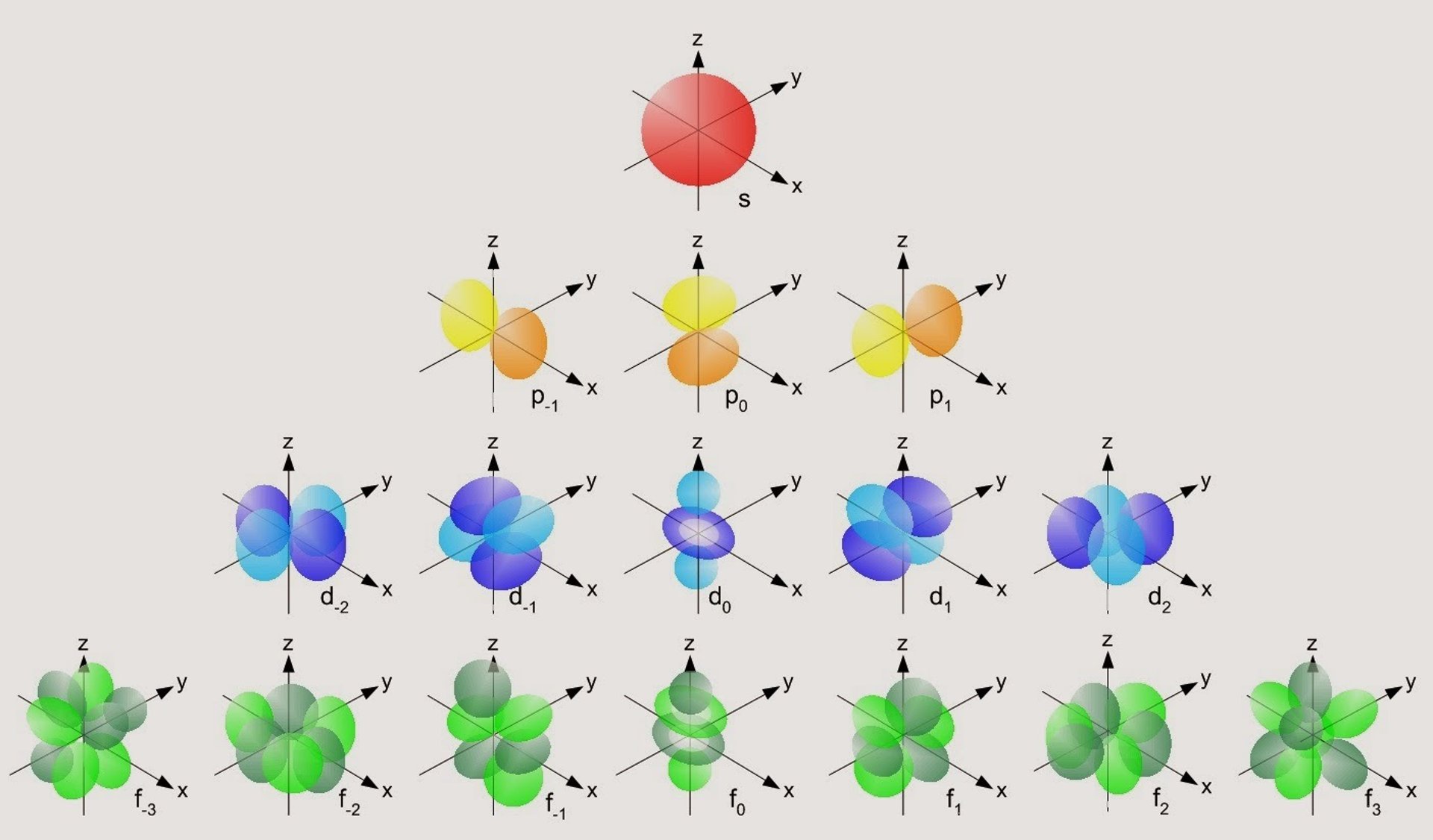

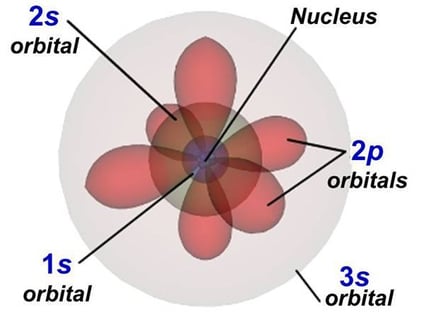

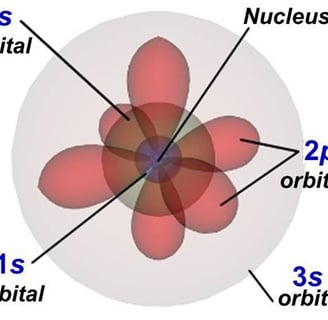

Representation of the shape of the orbitals on each floor.

Source: https://elfisicoloco.blogspot.com/2013/12/formas-de-los-orbitales-atomicos.html

Order of filling of the floors, following

the zigzag line. Source:

https://byjus.com/chemistry/aufbau-principle/

Seats and Hund's rule

Once you're on the floor that suits you best, you reach what might be the most stressful part of the whole process: choosing a seat.

The first passenger to arrive won’t have much trouble deciding and will probably pick the closest available seat. The interesting part comes when more passengers board the atomic bus: the new arrivals will sit in pairs of seats that are still empty, avoiding bothering the passengers already seated and making sure they can get comfortable.

And, of course, electrons do the same!

This “quirk” that electrons have of avoiding each other is known as Hund’s Rule, and it allows them to experience less electrical repulsion from the other electrons in the atom by being well distributed across the different orbitals (or seat pairs) on the same floor.

But... what happens when all the seat pairs already have one passenger?

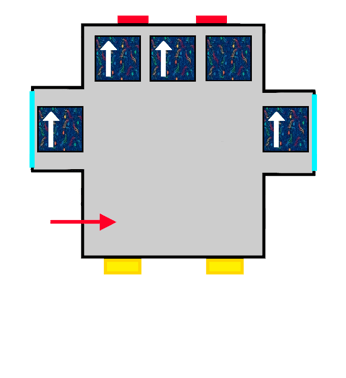

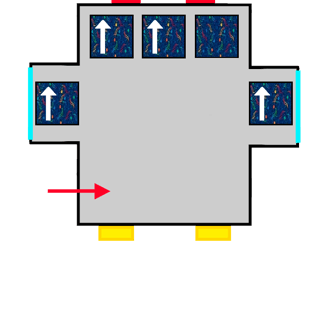

A bus with ALSA-style upholstery gradually filling up with people represented by arrows.

Comfort and Pauli exclusion principle

Just like bus passengers, poor electrons have no choice but to share a seat when all the others are taken. But there’s a very important detail: they can’t sit in the same way as the electron already occupying the orbital—or, in our analogy, as the passenger already seated. This happens because of the Pauli Exclusion Principle, which states that no two electrons can exist in the same quantum state.

In simpler terms, it means that two electrons can’t have all the same properties and be in the same place at the same time. They can’t be identical in the same spot, so when they share a seat (orbital), one of their properties must be different from the one already sitting there — specifically, their spin must be opposite.

The answer is spin. Spin is a very complex quantum property that represents the intrinsic rotation of the electron — something like the amount of rotational energy it has by itself — and it's closely related to magnetic fields. We’ll explore it in more detail in another article, but for now, the important thing to know is that this property must be different for electrons sharing the same orbital.

So the electrons that arrive first in the orbital settle in with a positive spin (an upward arrow), nice and comfortable, while the second has no choice but to take on a negative spin (a downward arrow), more squeezed in and tight.

The same thing happens with our passengers: the first one gets really comfortable since they arrived first, so the second can’t spread out as much or get as cozy—they’ll have to squeeze in and be a bit less comfortable.

In this way, electrons fill up the orbital they’re in completely, until there are no more free seats on the floor, and if there are more, they move on to the next one, following exactly the same rules—or quirks.

The same bus with ALSA upholstery filling up with the last passengers coming on board.

An example with a real element!

The bus analogy is great, but maybe you’re curious to see an example using a real element, to get a better idea of what atoms are actually like. Because of course, with everything we’ve seen so far, Rutherford’s planetary model doesn’t make much sense anymore.

Let’s take an example with neutral Oxygen, a classic oxygen atom. It has 8 protons and 8 electrons around the nucleus. In the image on the right, you can see the shapes of the orbitals — that is, the regions where electrons can be found.

The orbitals we call s are spherical—they’re the two gray ones in the image—while the p orbitals have a figure-eight shape and are the three red ones.

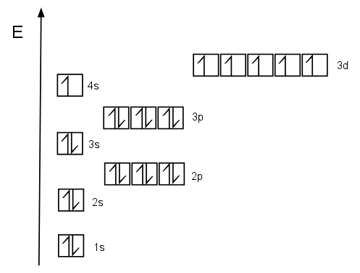

Let’s look at how we’d fill these orbitals using the same little arrows we used on the bus:

The first orbitals to be filled are 1s, 2s, and 2p. The s orbitals, the spherical ones, can hold only 2 electrons, while the p orbitals, with their lobe shapes, can hold 6.

Just like in the bus example, the 1s floor fills up first with two electrons —one “comfortable” and the other “more squeezed in.” The same happens on the next floor, 2s, and then we begin filling the third floor, 2p.

Each electron takes its own space, nice and comfy, with its spin pointing up. But the 8th electron, the last one in the oxygen atom, has no choice but to sit next to another electron, since there’s no more free space on that floor.

The first 4 orbitals of an atom: 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s. The numbers represent the “floor,” and the letter represents its shape.

https://chemistryfromscratch.org/2-3

Animation showing how the different orbitals of an oxygen atom are filled

Source: https://chem.libretexts.org/ (modified)

In this way, all the electrons in Oxygen have arranged themselves in the way that gives the atom the most stability — or in other words, in its lowest energy configuration. Although, as always, there are exceptions. Some elements are so peculiar that their electrons break these rules in order to minimize the atom’s energy even further. But… how can that be?

The exception that proves the rule: Chromium

These peculiar elements would be like a bus with a peculiar shape. Because of the number of electrons (passengers) it has, and the specific structure of the atom (bus), the most optimal arrangement is not to follow the usual rules and quirks.

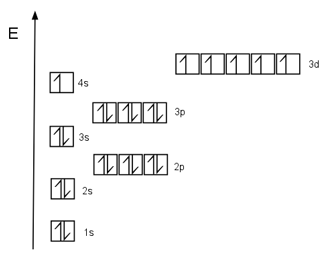

An example of this is Chromium. This element has 24 protons in its nucleus, so it has 24 electrons in its orbitals. Its electronic configuration is the following:

You’ve probably noticed—the 4s level is missing an electron! According to the rules we’ve seen, the last electron that’s now in the 3d orbital should actually be in the 4s, with its spin pointing down (or more "squeezed in").

How do they do it?

What is different?

Imagine that the shape of our bus is a bit peculiar. All the floors from 1s up to 4p have the usual typical rectangular shape, but the 3d floor has a special shape with two side extensions.

Orbital diagram of Chromium.

Okay, yes—it’s an aberration.

But the important thing is that it makes sense! (and ALSA seats!)

If there were only 4 electrons to place, starting with the first seats, the seats would look like you see in the image. This bus looks a bit unbalanced—it’s heavier on the left side, and with this strange shape it would easily become unstable. That’s why it’s better for an electron from the lower floor, the 4s, to move up and take the free seat, balancing the whole bus—that is, the whole atom.

Now, stepping away from the bus analogy: since the 3d orbital has 5 pairs of seats (10 total spots), it’s much more stable to have this orbital half-filled (5 out of 10 electrons) rather than leaving a gap. This way, the electrical repulsions between electrons are minimized because they are arranged in a much more symmetrical way.

The sociability of electrons doesn’t end here…

Just like we all have our quirks when choosing a seat, electrons follow their own rules when distributing themselves in atomic orbitals. From occupying the lowest energy levels first to spreading out as comfortably as possible, humans surprisingly show behaviors quite similar to electrons. Even in special cases where the rules seem to break, like with Chromium, there’s a logic behind it. Nature always seeks the most stable and efficient configuration.

But it doesn’t end here. Electrons also have their own preferences when atoms interact with each other, or even when they’re all alone and not part of any atom. Can you imagine how electrons behave in these situations? Don’t worry—we’ll discover that in upcoming articles!